60 biggest banks invested $705bn in fossil fuels last year

13 May 2024

Article written by Tim Mooney

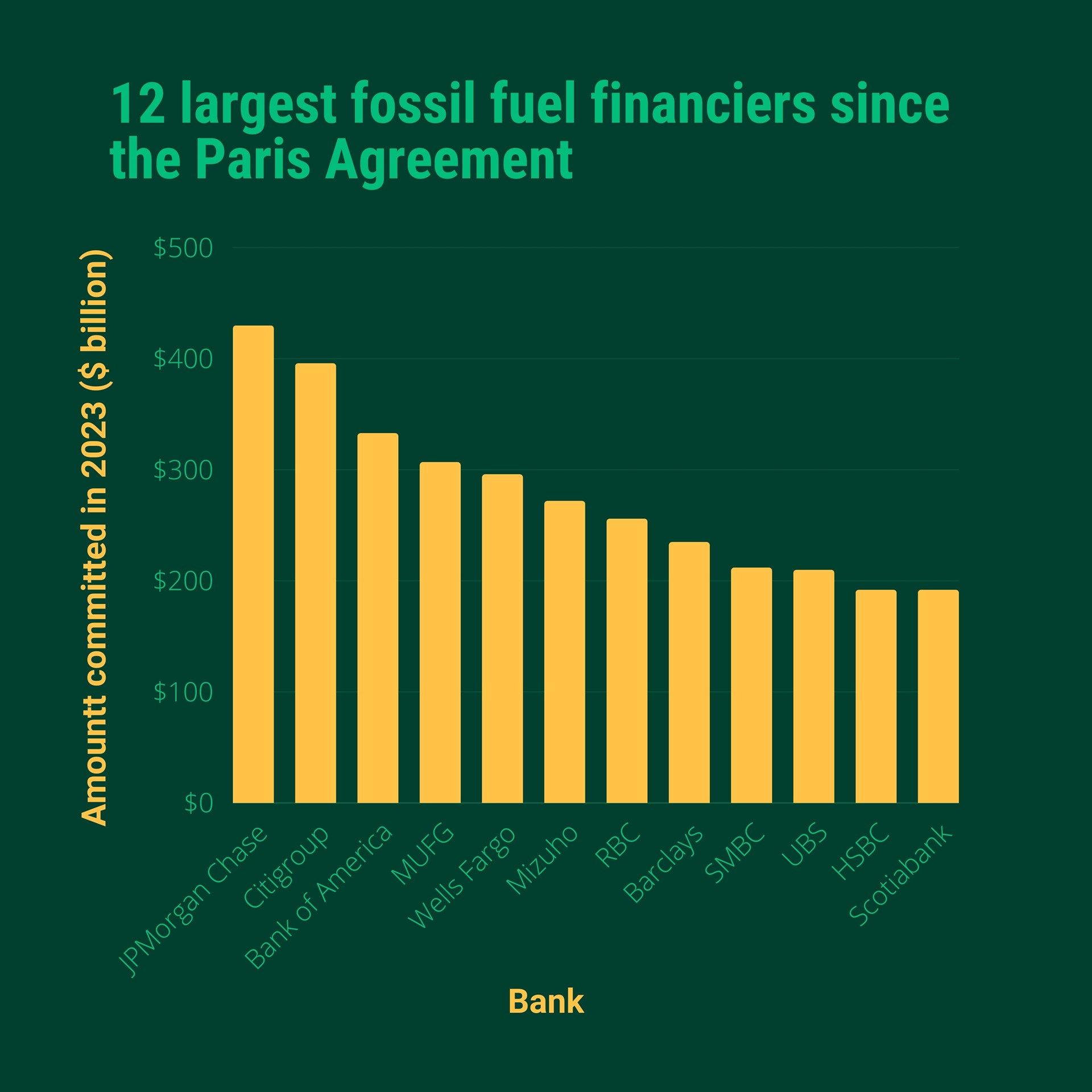

According to a new report from Banking on Climate Chaos, the 60 biggest banks globally invested $705bn in fossil fuel companies in 2023, bringing the total amount invested since the Paris Agreement to $6.9trn.

When analysing the breakdown of where these investments are going, these banks committed $347bn in 2024 to fossil fuel expansion companies, which are companies who invest heavily in the development and progression of fossil fuels. 2023 also saw these banks commit $121bn to finance companies with methane gas import and export capacity under development, and $63.3bn to finance acquisitions within the oil and gas industry.

Of all the fossil fuel financing by dollar value issued in 2023, 15.4 per cent matures after 2030, and 3.7 per cent matures after 2050. Given the targets outlined by the Paris Agreement and a climate movement urging for the phase out of fossil fuels, fossil fuel financing that matures after 2030 faces a significant risk of becoming stranded, and financing which matures after 2050 raises serious questions about certain banks and their long-term attitudes towards the climate movement.

North American and Japanese banks dominate the league table as the heaviest fossil fuel investors.

Of the 60 banks analysed, JPMorgan Chase is the biggest fossil fuel investor, injecting $40.875bn into the industry in 2023. They are closely followed by Citigroup with $30.27bn, and Bank of America with $33.682bn. Barclays remains Europe’s biggest fossil fuel financers having invested $24.22bn in 2023.

Overall, 33 banks of the top 60 decreased their financing for companies with fossil fuel exposure between 2022 and 2023, while 27 banks increased their financial commitments to fossil fuels over the same period. For the majority of these banks, the driver of this increase was investments in liquefied methane gas (LNG) which includes fracking, import and export, transport, and gas-fired power.

However, critics of the report have warned that the methodology relies on reporting on deals from researchers such as Bloomberg and Refinitiv who do not have a detailed view of who is leading the financing and where it is going.

It can be argued that loans, bond issues and underwriting arrangements involve several banks at times, so it’s difficult to determine how involved each bank is. It is also the case that financing channelled into fossil fuel companies to fund transition technology couldn’t be distinguished from financing of new oil and gas, for example.