The Circular Economy, environmental law and the priorities for green tech businesses

Read time: 5 minutes

Post-Brexit changes to waste and recycling targets will impact how businesses use resources in future. Amy House, Director of Green Economy explores the implications.

The UKs exit from the European Union was a catalyst to establish the future of environmental law. The government introduced a landmark Environment Bill to fill the legal gaps left when the EU Transition period ended, introducing a new cycle of setting legally-binding, long-term targets on environmental protection.

The targets focused on four priority areas: resource efficiency and waste reduction, air quality, water and biodiversity. Each target will be reviewed on a five-yearly basis and will be used to drive national policy, stimulate investment in green technology and provide long-term certainty for businesses.

The final targets will be subject to public consultation and won’t be in place until October 2022, so there’s still a lot to be decided. But one thing we can be sure of is the general direction of travel for waste and the circular economy.

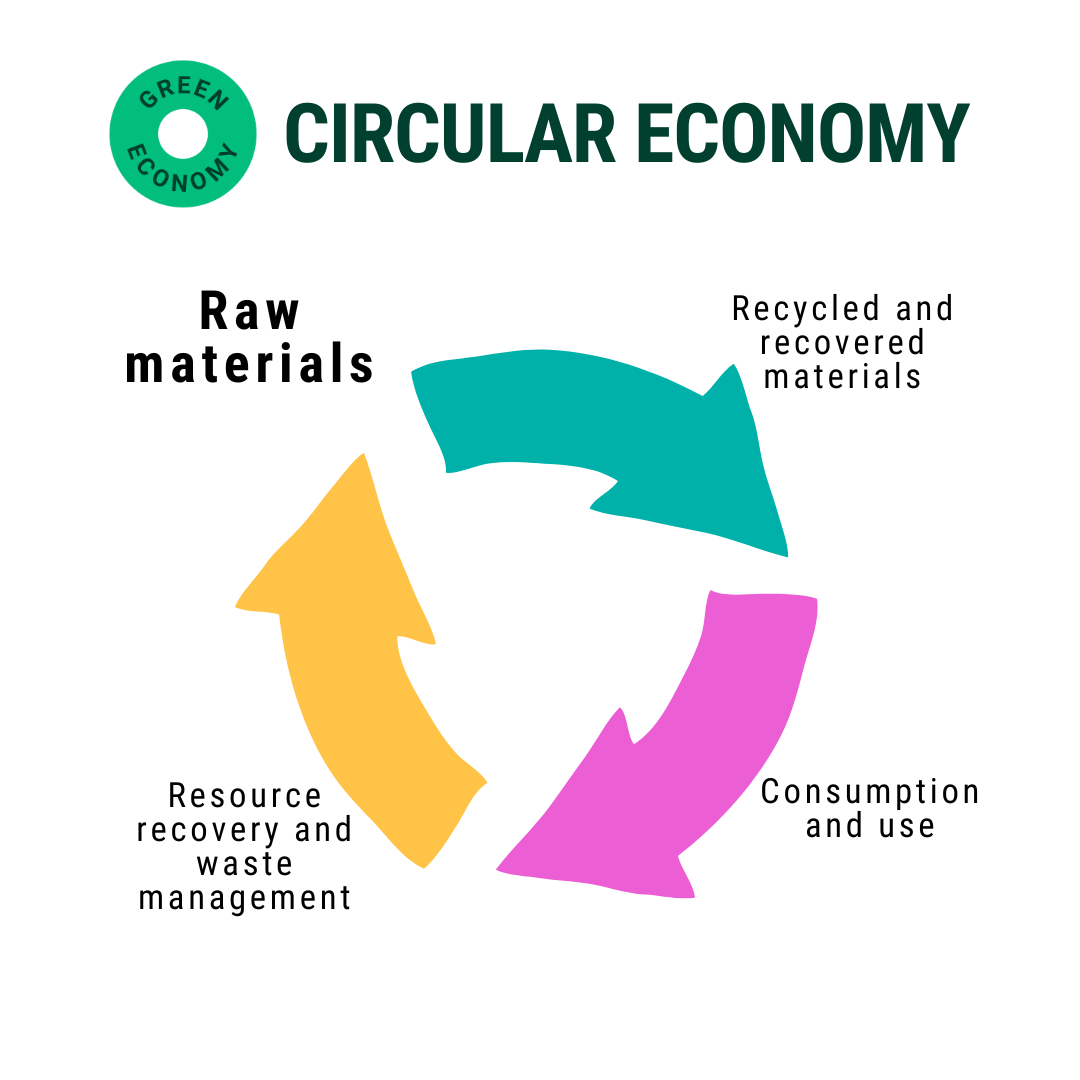

The UK will remain largely aligned with the EU’s Circular Economy Package – a group of legislative changes that aim to create a more sustainable economy that keeps materials in use for as long as possible.

The Circular Economy Package commits the UK to a number of legally-binding, long-term targets. The primary target is to recycle 65 per cent of municipal waste by 2035, with no more than 10 per cent of municipal waste going to landfill. It also restricts the materials that can be landfilled or incinerated, paving the way for materials to be kept in circulation rather than being burned or buried.

We’re a long way off these targets at the moment. Recycling levels have stalled at around 44 per cent in recent years. That’s below the EU average, and the UK will almost certainly miss its current EU target of a 50 per cent recycling rate this year. In other words, there’s lots of work to do.

Recycling two-thirds of our waste within 15 years will require a lot of government intervention and increased pressure on businesses to reduce waste and switch to more sustainable materials. That means change throughout the value chain, from the product design stage right through to what happens at the end of its life. Innovative new business models will be needed, such as incentivised returns or selling products as a service, along with a much larger UK recycling sector.

The forthcoming Environment Bill sets out the starting points for this journey. The Bill will give the government new powers to:

More detail on how these powers may be exercised in practice can be found in the government’s 2018 Resources and Waste Strategy. In the near-term, packaging – and plastic packaging in particular – is a key focus.

A new extended producer responsibility arrangement for packaging is earmarked for 2023. Under the current scheme, businesses that have a turnover of more than £2 million and produce or handle 50 tonnes of packaging a year or more have to pay into a compliance scheme to meet their share of the UK’s recycling targets. However, it only recovers around 10 per cent of the costs of managing the UK’s packaging waste – the rest of the bill is footed by the taxpayer.

The new scheme will set out to recover the full net costs of dealing with end-of-life packaging. This means companies paying into the scheme will pay higher charges for the disposal of their packaging, with modulated fees so those using recycled or recyclable materials will pay less.

The government has also committed to introducing a new tax on businesses who produce or import plastic packaging that does not contain at least 30 per cent recycled content.

Introducing producer responsibility to new sectors

There are currently four extended producer responsibility schemes in place in the UK, covering packaging, end-of-life vehicles, batteries, and waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE).

However, the government wants to create new schemes for other waste streams. Among the current priorities are textiles and clothing, and bulky items such as mattresses, furniture and carpets.

Powers in the Environment Bill will also mean that producer responsibility obligations can be expanded to include the prevention of waste or the redistribution of surplus materials. This would allow more action to be taken on reducing food waste in the food and drink industry – another waste stream that is high on the agenda.

Minimum eco-design requirements for certain products have existed at the EU level for several years. Historically, these have focused on minimum energy efficiency ratings for energy-using products such as lightbulbs and white goods. However, the EU is now planning to expand the concept to the circular economy by establishing minimum standards for durability, recyclability or reparability.

The UK has previously committed to “match or exceed” the EU’s eco-design rules, for example by setting minimum requirements for resource-intensive products like textiles and furniture.

Shifting to a circular economy will require a total transformation of our existing waste infrastructure. The measures we’re starting to see at a national level – and those still to come – will increase both the supply of recyclable materials to re-processors, and the demand for secondary materials on the market. This should lead to increased investment in the waste sector and encourage the creation of innovative new waste businesses and services.

According to waste charity WRAP, a circular economy could add £75 billion to the economy and create up to half a million new jobs. As always, the devil will be in the detail and there’s a huge amount of work to be done, but the road ahead is gradually becoming clearer. Green Economy will be on hand to help businesses to navigate the targets as they land.

If you operate in the waste and recycling sector join Green Economy to raise the profile of your business and access new market opportunities.